By the eighteenth century, Ohlone and other Native people in the Berkeley area were joined by European, Africans, and Native people from other areas of the Western Hemisphere who were operating under the Spanish crown. This so-called “historical period” marks the beginning of great social, cultural, ethnic, and landscape changes that would culminate in present-day Berkeley, California.

Spanish and Mexican Period (1542-1848)

The area that is now California was claimed by the Spanish Empire in 1542 after being discovered by the explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo. However, it was not until the first inland exploration of California, the Portola Expedition (1769), that the San Francisco Bay was discovered. In 1776, Juan Bautista de Anza led another expedition into California with the goal of establishing a more prominent Spanish claim to the land. In that same year, the San Francisco Mission (also known as Mission Dolores) was established and was tasked with maintaining a settlement and ‘civilizing’ the native population. Although the Mission did not use the land in what is now the East Bay, it is likely they gathered indigenous peoples from this locale (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009).

In 1820, the Alta California Governor Don Pablo Vicente de Sola granted a 44,800 acre tract of land, called the Rancho San Antonio Land Grant, to Don Luis Maria Peralta, a member of the de Anza expedition who helped found multiple missions and settlements. After Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1822, the Mexican government honored the Peralta Land Grant. This grant encompassed much of Alameda County and was divided into four separate estates for his sons in 1842 with the City of Berkeley within Jose Domingo Peralta’s estate. Until about 1850, the only people who resided on this tract was Jose Domingo, his family, and the ranch retainers. It is worth noting that none of the structures built in Berkeley during this time were near People’s Park (Chapman 1921, Hittell 1885).

After the Mexican-American War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo stated that the United States would honor Mexican land agreements, but the passing of the 1851 U.S. Federal Land Act required land owners to prove their titles in court. Over the next decade, a series of litigation with the US government and amongst the descendants of Don Luis Maria Peralta cost Domingo Peralta (as well as the other brothers in the East Bay) a fortune and they lost significant portions of their land. In addition, a large amount of squatters during the 1850’s also reduced Domingo’s property from its original 12,000 acres to a mere 30 acres (Hittell 1885). By the time of Domingo’s death in 1865, he no longer owned any land and was so poor he could not even afford a headstone. His wife and 10 children were evicted from their house in 1872, ending any remnants of the original Mexican occupation of the East Bay.

The American Period (1868-Present)

In the vicinity of the project area, the late 19th century was marked by the historic creation of the University of California (U.C.) public university system in 1868. The system succeeded the previously short-lived College of California, which was originally located in Oakland, California (Wollenburg 2008). With the failure of the College of California, the trustees decided that along with the new mission standard of emphasizing a liberal arts education, the first university within the system would now be located in Berkeley, California in 1873 (Wollenburg 2008). The site of the College of California is now a California Historical Landmark of Oakland (No. 45).

With the creation of the university, the city of Berkeley began slowly expanding most notably, in the downtown area of Berkeley and in the immediate vicinity surrounding the campus. This meant the construction of new residential housing communities, student dormitories, and city infrastructure and facilities. At this time, the Central Pacific Railroad extended into Downtown Berkeley creating the Berkeley Branch Railroad in 1876, which ran adjacent to the campus (Dunscomb 1967).

Berkeley and the greater Bay Area would be hit with two tremendous disasters during the first quarter of the 20th century. The first being the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. The earthquake occurred on April 18, 1906, registering an estimated magnitude of 7.8. According to the USGS Shake Quake Map and Station List, the Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) for Berkeley registered an eight on the scale (Boatwright and Bundock 2005; Lawson 1908). Although the earthquake and subsequent fires destroyed nearly the entirety of San Francisco and resulted in massive casualties, Berkeley sustained minimal to no physical damage or loss of life. Hundreds of thousands of San Franciscans became homeless and many of whom evacuated the city sought refuge in Oakland and Berkeley. Berkeley’s population rose from 13,214 in 1900 to a population of 56,036 by 1920 (Wollenburg 2008).

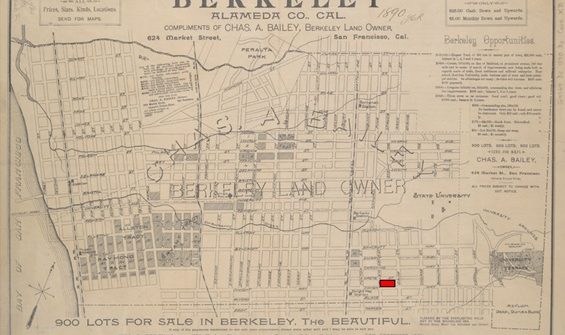

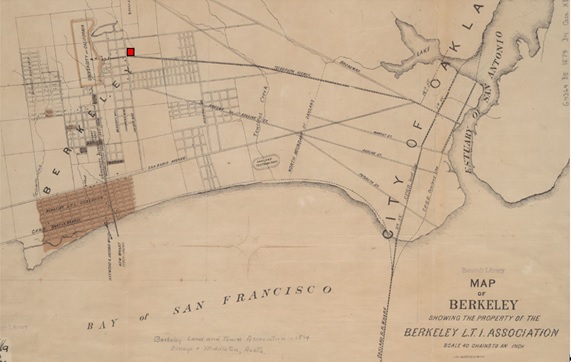

The residential area in the vicinity of People’s Park was created at the end of the nineteenth century. Streets that bound the park are depicted on Berkeley city maps as early as 1874 (Berkeley Public Library 2019). By 1890, the Berkeley Local Railroad Line brought commerce down what is now Telegraph Avenue and additional streets had been platted east of Telegraph and south of the University’s main campus. Retail venues evolved along the railroad route while residential buildings were constructed on lots not fronting Telegraph. A residential neighborhood composed of detached, single-family dwellings had arisen east of Telegraph by the 1910s. From the 1910s until the 1950s, multi-family apartment buildings were built on the lots in what is now People’s Park. Lots were consolidated and as this block became more densely inhabited.

References

Berkeley Public Library

1874 Map of Berkeley Showing the Property of the Berkeley L.T.I. Association.

http://cdn.calisphere.org/data/13030/fq/hb067n99fq/files/hb067n99fq-FID4.jpg Accessed January 31, 2019.

1890 Berkeley, Alameda County, California.

http://cdn.calisphere.org/data/13030/6h/hb4m3nb36h/files/hb4m3nb36h-FID7.jpg Accessed January 31, 2019.

Boatwright, John and Bundock, Howard

2005 Modified Mercalli Intensity Maps. 1906 San Francisco Earthquake ShakeMaps. Accessed. USGS 2018. Available online at the following link: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/events/1906calif/shakemap/

Chapman, C. E.

1921 A History of California: The Spanish Period. Macmillan.

Dunscomb, Guy.

1967 A Century of Southern Pacific Steam Locomotives, 1862-1962 (Modesto, California: 1967). Berkeley Branch Railroad Cash Book. California State Railroad Museum and Library Archives. Online Archives of California.

Hittell, T. H. (1885). History of California (Vol. 2). NJ Stone.

Lawson, Andrew C. (1908). The California Earthquake of April 18, 1906: Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Commission. Publication 87. (Vol. 1-2). Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Lawson, Andrew C.

1908 The California Earthquake of April 18, 1906: Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Commission. Publication 87. (Vol. 1-2). Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Lightfoot, Kent and Otis Parrish. (2009). California Indians and Their Environment. University of California Press.

Wollenburg, Charles M.

2008 Berkeley: A City in History. University of California Press. 1st Ed.