The period between 1960 and 1980 in Berkeley was marked by student-led protests, which attracted extensive media attention locally and nationally and vocalized Berkeley’s liberal and left-leaning views about social, civil, and environmental justice. The creation of public parks through activism like Chicano Park in San Diego, Poor People’s Park in Chicago, and Walden Park in Madison, Wisconsin was tangible result of widespread 1960s protests, which were part of larger anti-war and Civil Rights movements that rocked the United States at that time (Lovell 2018). The protests in Berkeley addressed those concerns while also contributing to ongoing local efforts to improve labor relations, address shifting housing and rent regulations, and increasing homelessness—topics that have been evergreen planks in Berkeley resistance ever since. The creation of People’s Park functioned as a site for displays of local activism.

The U.C. Berkeley found itself at the forefront of political activism by the 1960s. As the Vietnam War was churning abroad by 1961, while the Cold War crept into everyday lives of communities across the country. The United States government sponsored Cold War anti-communism efforts in the American mainland that involved committees designed to reveal communist sympathizers at home while it simultaneously fought a campaign against Civil Rights activists. In Berkeley, support for the Civil Rights Movement continued in the 1960s as students participated in voter registration drives in the southeastern United States. Berkeley students also took action against anti-communism hearings in the Bay Area by forming counter-protests and non-violent confrontations. This culminated in what would become the Free Speech Movement as students participated in numerous protests throughout the 1960s that forced University administration to acquiesce to student demands for equal rights, free speech, and an end to compliance with conservative anti-communism activities. Some of these protests were met with force by the University, City of Berkeley, and State of California (Glick 1984).

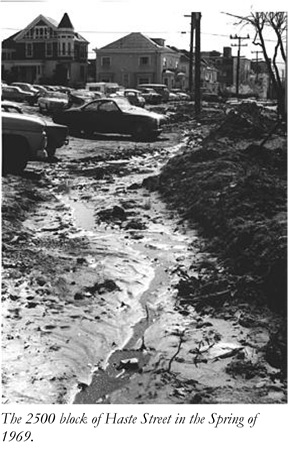

In 1952, the U.C. Berkeley Board of Regents adopted a plan for expanding the university to accept a 20,000 student enrollment celling. Twenty-five percent of students were to live in university housing under this plan, which meant the university would have to build additional housing. Land acquisition for this project was to focus on parcels immediately adjacent to campus south of Sproul Plaza. While several property owners held out during the 1950s, much of the housing acquired by the university in the target area was considered “blighted” as it had been allowed to deteriorate since its sale to the university. Parcels in what are now People’s Park were initially intended to become a fenced playing field as the university did not have the money to build the proposed student housing at that time. Between November, 1967 and July, 1968, houses and apartment buildings on the 2500 block of Haste Street were demolished or removed. Winter rains and budgetary shortfalls prevented the property from being turned into a playfield. By the spring of 1969, students and local residents began using the dirt block as an informal parking lot (Glick 1984).

Plans to turn this lot into a public park was launched and led by an ad-hoc group of counterculture youth. Berkeley had become central to the counterculture movement by the 1960s. Thousands of young people had moved to the city for college as well as to live a lifestyle dedicated to opposing the status quo of American society. Some of these individuals decided to turn the cleared area on Haste Street into a public park. On April 20, 1969, a group of about 200 activists begun clearing debris and laying sod along the easternmost section of what is now People’s Park. Construction continued for weeks without official sanction from the University. The University was slow to act but pressure to end the occupation centered around liability issues if any of the occupiers were to get hurt and drug use in the park. The local community and Berkeley administration resolved to deal with the matter peacefully as several previous protests had turned violent (Glick 1984)

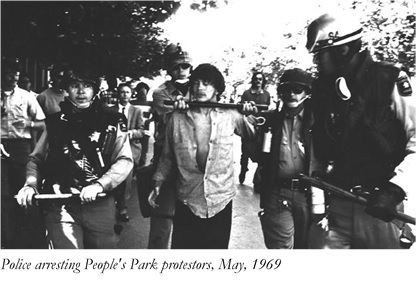

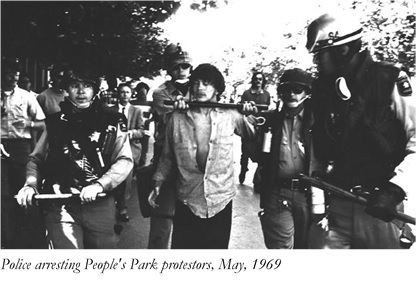

On Thursday, May 15, 1969, California Governor Ronald Reagan instructed police officers to clear the park. A large section of the improvements were demolished by bulldozers and the park was fenced to prevent public admission. By the afternoon, thousands of protesters had convened at the park. Officers attacked the crowd after protestors started throwing rocks and bricks. Law enforcement and protestors battled through the afternoon and into the night. The National Guard was called in along with additional law enforcement from the surrounding area. Law enforcement attempted to disperse the crowd using tear gas and shotgun fire, which resulted in the death of one U.C. Berkeley student who was shot by police. The protests and use of force continued until May, 30, 1969. Berkeley remained under National Guard control for months afterward and all forms of public dissent were crushed with force (Glick 1984).

In the summer of 1969, the University turned the property into a mixed-use parking lot with recreational facilities including volleyball and basketball courts, a softball field, and a fenced green space. Plans to build housing were shelved at that time. Local residents and students primarily boycotted the space into the 1970s. Following a new round of riots in 1972, the University agreed to lease the space to the City of Berkeley to be used as a park. An agreement was made on May 12, 1972 and almost immediately local residents started removing the existing infrastructure to create additional green space, plants, and gardens. People’s Park had finally become a reality but it was still avoided by most Berkelyites who avoided the space due to the drugs and vice that were associated with the counterculture (Glick 1984). This reputation as a space for deviance remains with the park today. Since the 1970s, the University has continued to make motions towards building student housing but none of these plans has come to fruition.

The proposed development of People’s Park in 2018 has garnered the attention and concern of both local Berkeley residents, activists, and the student and faculty population. This is part of Berkeley’s legacy of advocacy. People’s Park remains part of this important aspect of Berkeley’s past. The U.C. Berkeley’s Housing Task Force has proposed a development plan to build a student dormitory on the plot of land, to help account for the dearth of student housing for undergraduate students, particularly after their first year on campus (Hendricks 2017).

References

Glick, Stanley Irwin

1984 The People’s Park. Dissertation submitted to the Department of History, State University of New York, Stony Brook.

Hendricks, Shayann

2017 Oxford Tract stakeholders meet to discuss potential development of land. The Daily Californian. The Independent Berkeley Student Publishing Co., Inc.Lovell, Kera N.

2018 “Everyone gets a Blister”: Sexism, Gender Empowerment, and Race in the People’s Park Movement. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46(3&4): 103—119.